When

union violence Union violence is violence committed by unions or union members during labor disputes. When union violence has occurred, it has frequently been in the context of industrial unrest. Violence has ranged from isolated acts by individuals to wider campa ...

has occurred, it has frequently been in the context of

industrial unrest A labour revolt or worker's uprising is a period of civil unrest characterised by strong labour militancy and strike activity. The history of labour revolts often provides the historical basis for many advocates of Marxism, communism, socialism and ...

.

Violence has ranged from isolated acts by individuals to wider campaigns of organised violence aimed at furthering union goals within an industrial dispute.

According to labor historians and other scholars, the United States has had the bloodiest and most violent labor history of any industrial nation in the world, and there have been few industries which have been immune.

Researchers in industrial relations, criminology, and wider cultural studies have examined violence by workers or trade unions in the context of industrial disputes.

The US government has examined violence during industrial disputes.

Overview

According to a 1969 study, no major labor organization in American history has ever openly advocated violence as a policy, although some, in the early part of the 20th century, systematically used violence, most notably the Western Federation of Miners, and the International Association of Bridge Structural Iron Workers.

However, violence does occur in the context of industrial disputes. When violence has been committed by, or in the name of, the union, it has tended to be narrowly focused upon targets which are associated with the employer.

Violence was greater in conflicts in which there was a question of whether union recognition would be extended.

Union violence most typically occurs in specific situations, and has more frequently been aimed at preventing

replacement workers from taking jobs during a strike, than at managers or employers.

Protest and verbal abuse are routinely aimed against union members or replacement workers who cross picket lines ("blacklegs") during industrial disputes. The inherent aim of a union is to create a labor

monopoly

A monopoly (from Greek language, Greek el, μόνος, mónos, single, alone, label=none and el, πωλεῖν, pōleîn, to sell, label=none), as described by Irving Fisher, is a market with the "absence of competition", creating a situati ...

so as to balance the

monopsony

In economics, a monopsony is a market structure in which a single buyer substantially controls the market as the major purchaser of goods and services offered by many would-be sellers. The microeconomic theory of monopsony assumes a single entity ...

a large employer enjoys as a purchaser of labor. Strikebreakers threaten that goal and undermine the union's bargaining position, and occasionally this erupts into violent confrontation, with violence committed either by, or against, strikers.

Some who have sought to explain such violence observe, if labor disputes are accompanied by violence, it may be because labor has no legal redress. In 1894, some workers declared:

..."the right of employers to manage their own business to suit themselves," is fast coming to mean in effect nothing less than a right to manage the country to suit themselves.

A 1969 study of labor conflict violence in the United States examined the era following the 1947 passage of the Taft-Hartley Act, and concluded that violence had substantially abated. In the 16 years from 1947 through 1962, 29 people died in labor conflicts, a rate much lower than in previous eras. The study noted that attacks on strikers by company guards had all but disappeared. They estimated from NLRB records that 80 to 100 acts of violence by union members or supporters occurred each year, most of the attacks on people being unplanned fights with strikebreakers crossing picket lines. In the 1960s, the most common complaint of union violence was of sabotage during labor disputes. Numerous incidents included dynamite explosions, but targeting property, and without any dynamite-related injuries.

19th century

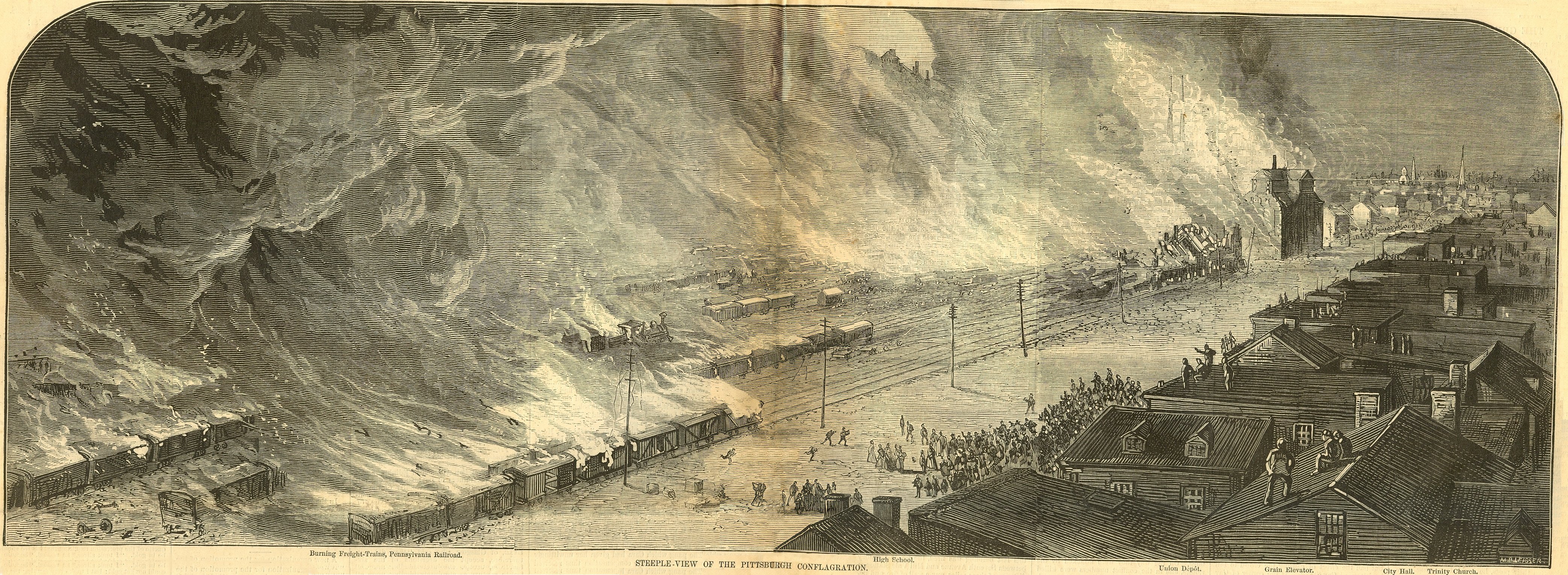

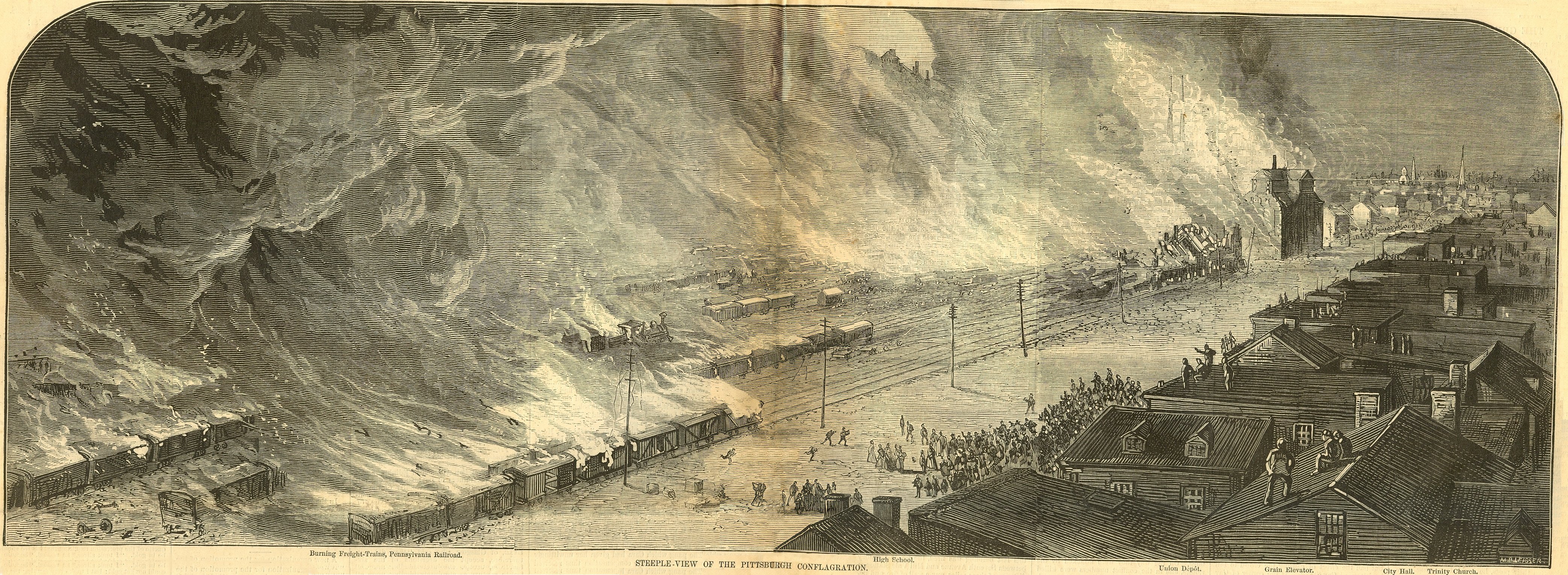

Great Railroad Strike of 1877

The great railroad strike of 1877 saw considerable violence by, and against, workers, and occurred before unions were widespread. It started on July 14 in

Martinsburg, West Virginia

Martinsburg is a city in and the seat of Berkeley County, West Virginia, in the tip of the state's Eastern Panhandle region in the lower Shenandoah Valley. Its population was 18,835 in the 2021 census estimate, making it the largest city in the E ...

, in response to the cutting of wages for the second time in a year by the

Baltimore & Ohio Railroad

The Baltimore and Ohio Railroad was the first common carrier railroad and the oldest railroad in the United States, with its first section opening in 1830. Merchants from Baltimore, which had benefited to some extent from the construction of ...

(B&O). Striking workers would not allow any of the stock to roll until this second wage cut was revoked. West Virginia governor

Henry M. Mathews sent in state militia units to restore train service, but the soldiers refused to use force against the strikers and the governor called for federal troops.

Violent street battles occurred in Maryland between the striking workers and the Maryland militia. When the outnumbered troops of the 6th Regiment fired on an attacking crowd, they killed 10 and wounded 25.

The rioters injured several members of the militia, damaged engines and train cars, and burned portions of the train station.

On July 21–22, the President sent federal troops and Marines to

Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

to restore order.

In Pittsburgh, strikers threw rocks at militiamen, who

bayoneted

A bayonet (from French ) is a knife, dagger, sword, or spike-shaped weapon designed to fit on the end of the muzzle of a rifle, musket or similar firearm, allowing it to be used as a spear-like weapon.Brayley, Martin, ''Bayonets: An Illustra ...

their antagonists, killing twenty people and wounding twenty-nine others.

In

Reading, Pennsylvania

Reading ( ; Pennsylvania Dutch: ''Reddin'') is a city in and the county seat of Berks County, Pennsylvania, United States. The city had a population of 95,112 as of the 2020 census and is the fourth-largest city in Pennsylvania after Philade ...

, workers conducted mass marches, blocked rail traffic, committed trainyard arson, and burned a bridge. The state militia shot sixteen citizens in the

Reading Railroad Massacre. The militia responsible for the shootings was mobilized by Reading Railroad management, not by local public officials.

Chicago was paralyzed when angry mobs of unemployed citizens wreaked havoc in the rail yards. The strike was eventually suppressed by thousands of vigilantes, National Guard, and federal troops.

Haymarket affair of 1886

In 1886 the

Haymarket affair

The Haymarket affair, also known as the Haymarket massacre, the Haymarket riot, the Haymarket Square riot, or the Haymarket Incident, was the aftermath of a bombing that took place at a labor demonstration on May 4, 1886, at Haymarket Square (C ...

(also known as the Haymarket massacre or Haymarket riot) was a protest rally and subsequent violence on May 4 at the Haymarket Square in

Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

. The rally supported

striking workers. When

police

The police are a constituted body of persons empowered by a state, with the aim to enforce the law, to ensure the safety, health and possessions of citizens, and to prevent crime and civil disorder. Their lawful powers include arrest and t ...

began to disperse the public meeting, an unknown person threw a dynamite

bomb

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the Exothermic process, exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-t ...

into their midst. The bomb blast and ensuing

gunfire

A gunshot is a single discharge of a gun, typically a man-portable firearm, producing a visible flash, a powerful and loud shockwave and often chemical gunshot residue. The term can also refer to a ballistic wound caused by such a discharg ...

resulted in the deaths of eight police officers, mostly from

friendly fire

In military terminology, friendly fire or fratricide is an attack by belligerent or neutral forces on friendly troops while attempting to attack enemy/hostile targets. Examples include misidentifying the target as hostile, cross-fire while eng ...

, and an unknown number of civilians.

In the internationally publicized legal proceedings that followed, eight

anarchists

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not necessari ...

were tried for murder. Four men were convicted and executed, and one committed

suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

in prison, although the prosecution conceded none of the defendants had thrown the bomb.

The Haymarket affair is generally considered significant for the origin of international

May Day

May Day is a European festival of ancient origins marking the beginning of summer, usually celebrated on 1 May, around halfway between the spring equinox and summer solstice. Festivities may also be held the night before, known as May Eve. T ...

observances for workers. The causes of the Haymarket Affair are still controversial, but can be traced in part to an incident the previous day, in which police fired into a crowd of agitated workers during shift change at the McCormick Works, where the regular work force was on strike, and at least two workers were killed. In popular literature, the Haymarket Affair inspired the caricature of "a bomb-throwing anarchist."

Illinois Governor

John Peter Altgeld

John Peter Altgeld (December 30, 1847 – March 12, 1902) was an American politician and the 20th Governor of Illinois, serving from 1893 until 1897. He was the first Democrat to govern that state since the 1850s. A leading figure of the Progr ...

later pardoned the three living survivors of the Haymarket prosecution, concluding (as have subsequent scholars) that there had been a serious miscarriage of justice in their prosecutions.

Burlington strike of 1888

During

the 1888 strike against the

Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad

The Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad was a railroad that operated in the Midwestern United States. Commonly referred to as the Burlington Route, the Burlington, or as the Q, it operated extensive trackage in the states of Colorado, Illin ...

, workers were arrested for wrecking a train. When one of those arrested turned out to be a detective, organized labor complained that the detective had incited the others.

Labor unrest in 1892

"In the 1890s violent outbreaks occurred in the North, South, and West, in small communities and metropolitan cities, testifying to the common attitudes of Americans in every part of the United States."

Workers with different ethnic origins who worked under very different conditions in widely separated parts of the United States nonetheless responded with equal ferocity when unions came under attack.

"Serious violence erupted in several major strikes of the 1890s, the question of union recognition being a factor in all of them."

1892 in particular was a year of considerable labor unrest. Governors of five states called out the national guard and/or the army to quell unrest—against miners in East

Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

and in

Coeur D'Alene, Idaho

Coeur d'Alene ( ; french: Cœur d'Alène, lit=Heart of an stitching awl, Awl ) is a city and the county seat of Kootenai County, Idaho, United States. It is the largest city in North Idaho and the principal city of the Coeur d'Alene Metropolita ...

, where a

shooting war followed the discovery of a

labor spy

Labor spying in the United States had involved people recruited or employed for the purpose of gathering intelligence, committing sabotage, sowing dissent, or engaging in other similar activities, in the context of an employer/labor organization r ...

, against switchmen in

Buffalo, New York

Buffalo is the second-largest city in the U.S. state of New York (behind only New York City) and the seat of Erie County. It is at the eastern end of Lake Erie, at the head of the Niagara River, and is across the Canadian border from South ...

, against a

general strike

A general strike refers to a strike action in which participants cease all economic activity, such as working, to strengthen the bargaining position of a trade union or achieve a common social or political goal. They are organised by large co ...

in

,

Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

, and against the

Homestead, Pennsylvania

Homestead is a borough in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, USA, in the Monongahela River valley southeast of downtown Pittsburgh and directly across the river from the city limit line. The borough is known for the Homestead Strike of 1892, an imp ...

steel strike.

Coeur d'Alene, Idaho labor strike

The strike of 1892 in

Coeur d'Alene, Idaho

Coeur d'Alene ( ; french: Cœur d'Alène, lit=Heart of an stitching awl, Awl ) is a city and the county seat of Kootenai County, Idaho, United States. It is the largest city in North Idaho and the principal city of the Coeur d'Alene Metropolita ...

erupted in violence when a union miner was killed by mine guards,

and was further inflamed when

union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

miners discovered they had been infiltrated by a

Pinkerton agent who had routinely provided union information to the mine owners.

On Sunday night, July 10, armed union miners gathered on the hills above the Frisco mine. More union miners were arriving from surrounding communities. At five in the morning, shots rang out, and the firing became continuous. Both sides blamed the other for starting the shooting. The union miners, exposed on the logged-off hillside, had not positioned themselves for a gunfight, while mine guards were able to shelter in buildings. The union men circled above the mill, and got into a position where they could send a box of

black powder

Gunpowder, also commonly known as black powder to distinguish it from modern smokeless powder, is the earliest known chemical explosive. It consists of a mixture of sulfur, carbon (in the form of charcoal) and potassium nitrate (saltpeter). Th ...

down the

flume

A flume is a human-made channel for water, in the form of an open declined gravity chute whose walls are raised above the surrounding terrain, in contrast to a trench or ditch. Flumes are not to be confused with aqueducts, which are built to tr ...

into one of the mine buildings. The building exploded, killing one company man and injuring several others. The union miners fired into a remaining structure where the guards had taken shelter. A second company man was killed, and sixty or so guards surrendered. Union men marched their prisoners to the union hall.

The violence caused the governor to declare Martial Law,

and bring in six companies of the

Idaho National Guard

The Idaho Military Department consists of the Idaho Army National Guard, the Idaho Air National Guard, the Idaho Bureau of Homeland Security, and formerly the Idaho State Guard. Its headquarters are located in Boise. The main goal of the Idaho M ...

to "suppress insurrection and violence." Federal troops also arrived, and they confined six hundred miners in

bullpens without any hearings or formal charges. Some were later "sent up" for violating injunctions, others for obstructing the United States mail.

Homestead Strike, and an assassination attempt

One of the most notorious incidents of violence against management occurred in 1892 during the

Homestead Strike

The Homestead strike, also known as the Homestead steel strike, Homestead massacre, or Battle of Homestead, was an industrial lockout and strike that began on July 1, 1892, culminating in a battle in which strikers defeated private security agent ...

—one of the most violent industrial disputes in American history—when

Alexander Berkman

Alexander Berkman (November 21, 1870June 28, 1936) was a Russian-American anarchist and author. He was a leading member of the anarchist movement in the early 20th century, famous for both his political activism and his writing.

B ...

attempted to assassinate

Henry Clay Frick

Henry Clay Frick (December 19, 1849 – December 2, 1919) was an American industrialist, financier, and art patron. He founded the H. C. Frick & Company coke manufacturing company, was chairman of the Carnegie Steel Company, and played a major ...

, chairman of the

Carnegie Steel Company

Carnegie Steel Company was a steel-producing company primarily created by Andrew Carnegie and several close associates to manage businesses at steel mills in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania area in the late 19th century. The company was forme ...

and manager of the mill where the strike occurred. Frick had locked out the workers, and later hired three hundred armed guards from the

Pinkerton Detective Agency

Pinkerton is a private security guard and detective agency established around 1850 in the United States by Scottish-born cooper Allan Pinkerton and Chicago attorney Edward Rucker as the North-Western Police Agency, which later became Pinkerton ...

to break the union's

picket lines, resulting in gunfire and flaming barges on the Ohio River. There was a consensus of all parties that the presence of the Pinkertons inflamed the attitudes of the strikers.

The strikers defeated the Pinkertons, but could not keep the mills from operating after the National Guard was deployed.

Berkman, an avowed

anarchist

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including, though not neces ...

, had no connection to the union involved in the strike, but believed he was acting in the workers' interests. He was motivated by newspaper reports of,

...Henry Clay Frick, whose attitude toward labor is implacably hostile; his secret military preparations while designedly prolonging the peace negotiations with the Amalgamated

Amalgamation is the process of combining or uniting multiple entities into one form.

Amalgamation, amalgam, and other derivatives may refer to:

Mathematics and science

* Amalgam (chemistry), the combination of mercury with another metal

**Pan ama ...

; the fortification of the Homestead steel-works; the erection of a high board fence, capped by barbed wire and provided with loopholes for sharpshooters; the hiring of an army of Pinkerton thugs; the attempt to smuggle them, in the dead of night, into Homestead; and, finally, the terrible carnage.

Berkman's attack, called an

attentat by the anarchists, injured but failed to kill Frick. Having anticipated that his act would launch a worker uprising, Berkman was surprised when a carpenter hit him with a hammer after he had been restrained. The attempted murder alienated the anarchist community from much of the labor movement, as well as dividing the anarchist community itself.

Frick had been widely hated, but in at least one analysis, becoming the victim of such an attack transformed him into a "folk hero" in the public view.

During the Homestead strike, Carnegie Steel Company employees in Duquesne joined the strike that was occurring across the river. A riot broke out, and a number of the workers were arrested. It turned out that two of the strikers were Pinkerton detectives, and convictions were secured.

Battle of Virden, 1898

In 1897, the Pana Coal Company attempted to import African-American strikebreakers. A train car was intercepted by armed striking miners, and the strikebreakers were sent home unharmed.

The following year, however, another company, the Chicago-Virden Coal Company, attempted a similar strike-breaking effort, this time with an armed escort on the train car. The result was called the

Battle of Virden

The Battle of Virden, also known as the Virden Mine Riot and Virden Massacre, was a labor union conflict and a racial conflict in central Illinois that occurred on October 12, 1898. After a United Mine Workers of America local struck a mine in Vi ...

. Guards fired their rifles as they disembarked from the train. In the ensuing gun battle, fourteen men, including eight strikers, were killed.

criticized the company, and called up the National Guard, who were able to restore order. The National Guard prevented a similar incident by turning away additional strikebreakers the day after the riot.

Coeur d'Alene, Idaho labor confrontation of 1899

In April 1899, as the

Western Federation of Miners

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was a trade union, labor union that gained a reputation for militancy in the mining#Human Rights, mines of the western United States and British Columbia. Its efforts to organize both hard rock miners and ...

(WFM) was launching an organizing drive of the few locations not yet unionized, superintendent Albert Burch declared that the company would rather "shut down and remain closed twenty years" than to recognize the union. He then fired seventeen workers that he believed to be union members and demanded that all other union men collect their back pay and quit.

On April 29, 250 angry union members belonging to the WFM seized a train in

Burke

Burke is an Anglo-Norman Irish surname, deriving from the ancient Anglo-Norman and Hiberno-Norman noble dynasty, the House of Burgh. In Ireland, the descendants of William de Burgh (–1206) had the surname ''de Burgh'' which was gaelicised ...

. At each stop through

Burke-Canyon

Burke Canyon is the canyon of the Burke-Canyon Creek, which runs through the northernmost part of Shoshone County, Idaho, U.S., within the northeastern Silver Valley. A hotbed for mining in the late-nineteenth and twentieth centuries, Burke Ca ...

, more miners climbed aboard. At Frisco, the train stopped to load eighty wooden boxes, each containing fifty pounds of dynamite. Nearly a thousand men rode the train to

Wardner, the site of a $250,000 mill of the

Bunker Hill mine

The Bunker Hill Mine and Smelting Complex (colloquially the Bunker Hill smelter) was a large smelter located in Kellogg, Idaho, in the Coeur d'Alene Basin. When built, it was the largest smelting facility in the world.National Research Council, 20 ...

. After carrying three thousand pounds of dynamite into the mill, they set their charges and scattered. Two men were killed, one of them a non-union miner, the other a union man accidentally shot by other miners. Their mission accomplished, the miners once again boarded the "Dynamite Express" and left the scene.

From Kellog to Wallace, ranchers and laboring people lined the tracks and, according to one eyewitness, "cheered the nionmen lustily as they passed."

Once again, miners were rounded up and herded into

bullpen

In baseball, the bullpen (or simply the pen) is the area where relief pitchers warm up before entering a game. A team's roster of relief pitchers is also metonymically referred to as "the bullpen". These pitchers usually wait in the bullpen if t ...

s and held there for months.

Early 20th century

Colorado Labor Wars of 1903-04

During the

Western Federation of Miners

The Western Federation of Miners (WFM) was a trade union, labor union that gained a reputation for militancy in the mining#Human Rights, mines of the western United States and British Columbia. Its efforts to organize both hard rock miners and ...

strike of 1903–04, there was considerable violence, including an explosion at the Vindicator mine which killed two, and an explosion at the Independence Depot which killed thirteen. The Cripple Creek Mining District was under occupation by the Colorado National Guard, the

Citizens' Alliance was active in the district, and historians continue to debate who was responsible for each incident of violence. One likely perpetrator was convicted assassin

Harry Orchard

Albert Edward Horsley (March 18, 1866 – April 13, 1954), best known by the pseudonym Harry Orchard, was a miner convicted of the 1905 political assassination of former Idaho Governor Frank Steunenberg. The case was one of the most sensational an ...

. A major in the National Guard later testified that the militia was responsible for orchestrated beatings of striking miners.

International Association of Bridge Structural Iron Workers, 1906-1911

Perhaps the most significant example of a campaign of union violence was carried out by the

International Association of Bridge Structural Iron Workers from 1906 to 1910. With the blessing and financial support of high-ranking leadership, the union set dynamite and nitroglycerine bombs at about 100 sites from 1906 to 1911, typically at construction sites using non-union workers. These series of attacks has been described as the largest

domestic terrorism

Domestic terrorism or homegrown terrorism is a form of terrorism in which victims "within a country are targeted by a perpetrator with the same citizenship" as the victims.Gary M. Jackson, ''Predicting Malicious Behavior: Tools and Techniques ...

spree in American history.

The bombings were carried out in retaliation against workplaces that used

open shop

An open shop is a place of employment at which one is not required to join or financially support a union (closed shop) as a condition of hiring or continued employment.

Open shop vs closed shop

The major difference between an open and closed s ...

policies (allowing non-union and union workers side by side, or prohibiting unions altogether), rather than

closed shop

A pre-entry closed shop (or simply closed shop) is a form of union security agreement under which the employer agrees to hire union members only, and employees must remain members of the union at all times to remain employed. This is different fro ...

s (union only). The bombs were purportedly placed with the intention of damaging property, not people, but several explosions injured people (e.g., "5 or 6" injuries at a

Hoboken, New Jersey

Hoboken ( ; Unami: ') is a city in Hudson County in the U.S. state of New Jersey. As of the 2020 U.S. census, the city's population was 60,417. The Census Bureau's Population Estimates Program calculated that the city's population was 58,690 i ...

construction site in the early morning of March 31, 1909), and on other occasions passersby or night watchmen came within minutes of being at the scene of explosions.

[ Approximately one hundred structures were damaged or destroyed by dynamite, including ]bridge

A bridge is a structure built to span a physical obstacle (such as a body of water, valley, road, or rail) without blocking the way underneath. It is constructed for the purpose of providing passage over the obstacle, which is usually somethi ...

s, viaduct

A viaduct is a specific type of bridge that consists of a series of arches, piers or columns supporting a long elevated railway or road. Typically a viaduct connects two points of roughly equal elevation, allowing direct overpass across a wide v ...

s, railroad track

A railway track (British English and UIC terminology) or railroad track (American English), also known as permanent way or simply track, is the structure on a railway or railroad consisting of the rails, fasteners, railroad ties (sleepers, ...

s and loaded rail cars, machine shop

A machine shop or engineering workshop (UK) is a room, building, or company where machining, a form of subtractive manufacturing, is done. In a machine shop, machinists use machine tools and cutting tools to make parts, usually of metal or plast ...

s, office buildings

An office is a space where an organization's employees perform administrative work in order to support and realize objects and goals of the organization. The word "office" may also denote a position within an organization with specific dut ...

, and warehouses

A warehouse is a building for storing goods. Warehouses are used by manufacturers, importers, exporters, wholesalers, transport businesses, customs, etc. They are usually large plain buildings in industrial parks on the outskirts of cities, town ...

in the states of Illinois

Illinois ( ) is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern United States. Its largest metropolitan areas include the Chicago metropolitan area, and the Metro East section, of Greater St. Louis. Other smaller metropolita ...

, Indiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

, New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

, Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The sta ...

, Iowa

Iowa () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States, bordered by the Mississippi River to the east and the Missouri River and Big Sioux River to the west. It is bordered by six states: Wisconsin to the northeast, Illinois to the ...

, Michigan

Michigan () is a state in the Great Lakes region of the upper Midwestern United States. With a population of nearly 10.12 million and an area of nearly , Michigan is the 10th-largest state by population, the 11th-largest by area, and the ...

, Wisconsin

Wisconsin () is a state in the upper Midwestern United States. Wisconsin is the 25th-largest state by total area and the 20th-most populous. It is bordered by Minnesota to the west, Iowa to the southwest, Illinois to the south, Lake M ...

, , New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

, Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

, California

California is a U.S. state, state in the Western United States, located along the West Coast of the United States, Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the List of states and territori ...

and Utah

Utah ( , ) is a state in the Mountain West subregion of the Western United States. Utah is a landlocked U.S. state bordered to its east by Colorado, to its northeast by Wyoming, to its north by Idaho, to its south by Arizona, and to it ...

.[ About a hundred non-union workers were assaulted. In the Chicago area alone, there were 12 dynamite attacks on non-union construction sites from 1906 to 1911, six of them taking place in 1910.

Harrison Gray Otis, publisher of the ]Los Angeles Times

The ''Los Angeles Times'' (abbreviated as ''LA Times'') is a daily newspaper that started publishing in Los Angeles in 1881. Based in the LA-adjacent suburb of El Segundo since 2018, it is the sixth-largest newspaper by circulation in the Un ...

, as a vocal opponent of labor unions. On 1 October 1910, a union dynamite bomb exploded at the Los Angeles Times building. The explosion and subsequent fire killed 21 Times workers, and injured 100 more.

The next day, a mysterious suitcase was found outside the home of Times publisher Otis; police moved the suitcase away from the building. When they opened it, they heard ticking, and ran. They were 60 feet away when the dynamite went off, creating a crater and rattling windows, but without injuring anyone. Another dynamite bomb was discovered and disarmed at the Los Angeles home of the president of the anti-union Merchants and Manufacturers Association.

The southern California crew of Ortie McManigal and James B. Macnamara were still not through, and set off eight more explosions, including a Christmas Day 1910 explosion at the Llewellyn Iron Works in Los Angeles.

Police found bomb-making equipment, including dynamite, at the Ironworkers Union office in San Francisco, and at the union headquarters in Indianapolis. Union member Ortie McManigal later confessed and testified against the others.McNamara, Ryan, Clancy, Butler, Morrin and the others may have done what they thought they had to do to preserve the International Association. And despite other consequences of the dynamite campaign, they did save the Union. The International Officers stretched the limits of zeal in a righteous cause. Their strategy and tactics suffered - not the cause or validity of unionism.

Battle of Blair Mountain, 1921

Two years of conflict between miners and mine owners, characterized by utilization of the Baldwin–Felts Detective Agency

The Baldwin–Felts Detective Agency was a private detective agency in the United States from the early 1890s to 1937. Members of the agency were central actors in the events that led to the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1921 and violent repression ...

for infiltrating, sabotaging and attacking the United Mine Workers union, culminated in the Battle of Blair Mountain in 1921. The largest armed insurrection since the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

was touched off by the murders of Sid Hatfield and Ed Chambers on the courthouse steps of Welch, West Virginia

Welch is a city located in McDowell County in the State of West Virginia, United States. The population was 3,590 at the 2020 census, however the 2021 census estimate put the population at 1,914, due to the McDowell Prison complex in the north ...

.coal miner

Coal mining is the process of resource extraction, extracting coal from the ground. Coal is valued for its Energy value of coal, energy content and since the 1880s has been widely used to generate electricity. Steel and cement industries use c ...

s from throughout West Virginia who fought the coal company's hired guns and their allies, the state police for three days before federal troops intervened.

The Herrin Massacre, 1922

Williamson County, Illinois, a county with a "unique history of violence" for a rural county, was the location of the Herrin Massacre, one of the most horrific and perplexing incidents of union violence.

Late 20th century

1979 Imperial Valley Lettuce Strike

The United Farm Workers

The United Farm Workers of America, or more commonly just United Farm Workers (UFW), is a labor union for farmworkers in the United States. It originated from the merger of two workers' rights organizations, the Agricultural Workers Organizing ...

1979 strike against Imperial Valley lettuce growers was organized by Cesar Chavez

Cesar Chavez (born Cesario Estrada Chavez ; ; March 31, 1927 – April 23, 1993) was an American labor leader and civil rights activist. Along with Dolores Huerta, he co-founded the National Farm Workers Association (NFWA), which later merged ...

to dispute wages for produce workers. Despite his outspoken calls for peaceful protests and the UFW's policy of non-violence, several instances of widespread violence and damage occurred during the strike. "UFW pickets engaged in rock-throwing, blocking access to and from grower facilities or fields, rushing into fields towards replacement workers, throwing nail-type devices on the ground to cause flat tires in grower vehicles, overturning grower vehicles, carrying or using sticks, clubs, sling shots or other weapons.....There was evidence that the picket captains urged strikers to throw rocks and to vandalize grower equipment. There was evidence that King and the picket captains made threats to kill the replacement workers. There was evidence that the UFW could discipline picketers who violated strike rules by pulling them off the picket line and having them work elsewhere yet the evidence tended to show the UFW rarely disciplined picketers....There was testimony picket captains encouraged strikers to throw rocks and vandalize grower equipment. In particular, there was evidence of a "Fantasma" or "Phantom Crew" organized by the strikers to intimidate growers and replacement workers. This phantom crew was composed of five or six "real strong young men" who would use a black van at night to attack replacement workers and to vandalize irrigation equipment, vehicles and homes belonging to growers and replacement workers.

In the following years, a judge would later find the actions of the UFW were "acts of unlawful picketing" and held them financially liable for damages to the growers.

1985 Massey Energy strike

The United Mine Workers Union

The United Mine Workers of America (UMW or UMWA) is a North American labor union best known for representing coal miners. Today, the Union also represents health care workers, truck drivers, manufacturing workers and public employees in the Unite ...

1985 strike against Massey Energy included attacks on company vehicles with rifle fire. Trucks hauling coal from the mines were fired upon with rifles a number of times, and three drivers had previously been wounded by the rifle fire before June 1985, when another truck convoy was hit by rifle fire, killing driver Hayes West when his truck was hit by at least 21 rifle rounds, and the driver of another truck was wounded.

State and local law enforcement did not charge anyone in the death of Hayes West. Five members of the United Mine Workers Union, including Donnie Thornsbury, president of UMW Local 2496, were indicted by a federal grand jury, arrested, and charged with conspiracy to damage and disable motor vehicles used in interstate commerce. After a trial in federal court, four out of the five were convicted, including union official Thornsbury, and their convictions were upheld on appeal.

1986, Electrical Workers protest

During protests by the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers

The International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers (IBEW) is a labor union that represents approximately 775,000 workers and retirees in the electrical industry in the United States, Canada, Guam, Panama, Puerto Rico, and the US Virgin Islands; ...

Local 1547 against a non-unionized workforce getting a contract, picketers threatened and assaulted workers, spat at them, sabotaged equipment, and shot guns near workers.

1986/1987, Hotel Workers Strike

Three union workers set fire to the Hotel Dupont Plaza in San Juan, Puerto Rico, while other union members staged a fight as a distraction. The union, said to be affiliated with the Teamsters, was having a labor dispute with management over pay and health care. Ninety-seven people were killed, none of whom were union members. Most bodies were burned beyond recognition.

1989 Pittston coal strike

The 1989 strike by the United Mine Workers of America (UMWA) against the Pittston Coal Company's mines in Virginia and West Virginia was marked by shots fired at strikebreakers. In July 1989, a car bomb exploded in the parking lot of Pittston headquarters at Lebanon, Virginia

Lebanon is a town in Russell County, Virginia, United States. The population was 3,424 at the 2010 census. It is the county seat of Russell County.

History

The town of Lebanon was founded in 1818 as per an effort to create a new county seat ...

.

1990, New York Daily News Strike

On the first day of The ''New York Daily News

The New York ''Daily News'', officially titled the ''Daily News'', is an American newspaper based in Jersey City, NJ. It was founded in 1919 by Joseph Medill Patterson as the ''Illustrated Daily News''. It was the first U.S. daily printed in ta ...

'' strike, delivery trucks were attacked with stones and sticks, and in some cases burned, with the drivers beaten.

1993 Arch Mineral Corporation strike

Eight members of the striking United Mine Workers Union were arrested after Eddie York was shot and killed in Logan County, West Virginia, as he drove away from the coal mine, through the picket line. York, an employee of an environmental contractor, was at the mine to perform government-mandated maintenance of sedimentation ponds, work unrelated to the labor dispute. In the same incident, a truck driven by a mine guard was struck by rocks thrown by strikers on the picket line, which smashed the windshield. Howard Green, a member of the UMW executive board, accused Arch Corporation mine guards of murdering York, to give bad publicity to the union.

1997, Teamsters Union strike against UPS

In Miami, during a 1997 Teamsters Union strike against UPS, a group of men pulled UPS truck driver Rod Carter out of his truck, beat him, and stabbed him six times with an ice pick. Carter had earlier received a threatening phone call from the home of Anthony Cannestro, Sr., president of Teamsters Local 769.[

]

21st century

Laborers Local 91, Niagara, New York, 1995-2001

For years, officials of Laborers Local 91, in Niagara, New York, directed a strongarm squad of union members to make death threats and to commit criminal acts against nonunion construction workers and work sites. In 1997, the union fire-bombed a residence used by non-union workers in Niagara Falls, New York, causing permanent injury to one of the inhabitants. In 1998, union members attacked four tile-layers at a supermarket construction site, beating them so badly that they were all hospitalized, one so badly that he had not returned to work four years later.

State and local law enforcement did not charge anyone in the beatings. After a four-year federal investigation, the FBI arrested 14 union members for the violence, including the local's vice president, business manager, assistant business manager, and a former president. Andrew Shomers confessed to the fire-bombing, and also to the beatings at the supermarket site. Another union member, confessed to driving the getaway car in the fire bombing.

Anthony Cerrone, a member of local 91, confessed to involvement in the supermarket attack and the fire-bombing.

2011, Longshoremen

It was reported on September 9, 2011, that members of the International Longshore and Warehouse Union (ILWU) frightened security guards, dumped grain, and vandalized property belonging to EGT, LLC, over a labor dispute. No one was hurt, and no one had been arrested at the time the incident was reported. District Judge Ronald Leighton later issued a preliminary injunction against the ILWU citing their reported behavior.

2012, Lansing, Michigan

Union workers protesting right-to-work legislation in Lansing, Michigan

Lansing () is the capital of the U.S. state of Michigan. It is mostly in Ingham County, although portions of the city extend west into Eaton County and north into Clinton County. The 2020 census placed the city's population at 112,644, making ...

destroyed a tent run by Americans for Prosperity

Americans for Prosperity (AFP), founded in 2004, is a libertarian conservative political advocacy group in the United States funded by Charles Koch and formerly his brother David. As the Koch brothers' primary political advocacy group, it is one ...

. People were inside the tent but managed to escape before the collapse. Additionally, hot dog stand operator Clinton Tarver, a popular vendor around the Capital area who was hired to provide catering for AFP, lost his equipment, condiments, coolers, and food in the collapse. According to Tarver (an African American), union workers, who had incorrectly assumed he was supporting AFP, called Tarver an "Uncle Tom nigger". A union worker also punched conservative comedian and Fox News contributor Steven Crowder, resulting in a chipped tooth and a minor cut on the forehead. Another worker threatened to kill Crowder with a gun.

Ironworkers Local 401, Philadelphia, 2015

Although the violence, property destruction and arson had been going on for years, it intensified after the economic downturn of 2020–2021, as construction work became scarcer. In 2014, Ironworkers union members caused $500,000 in damage to the non-union construction site of a Quaker meetinghouse in Chestnut Hill. In another incident, Ironworkers beat nonunion workers outside a Toys-R-Us store with baseball bats. Some of the violence was directed at union construction sites staffed by other craft unions, such as the Carpenters Union, in an attempt to get the work for the Ironworkers.

After an FBI investigation, federal prosecutors filed racketeering and arson charges against ten officers and members of Ironworkers Local 401.

Carpenters Union, Philadelphia, 2015

In 2015, the Pennsylvania Convention Center Authority sued the Carpenters Union local in Philadelphia for racketeering, under the federal RICO statute. The Authority charged that the union had engaged in a pattern of "illegal and disruptive mass picketing and protests; physical intimidation, harassment, stalking, and assault and battery; verbal intimidation, harassment, race-baiting, and threats; and the destruction of property." The Carpenters Union denied the charges.

Union-on-union violence

Sometimes, unions are accused of violence or threats of violence by other unions.

Railroad Trainmen versus Street Railway Employees, 1940

In June 1940, a bus driver member of the Amalgamated Association of Street Railway & Motor Coach Employees, which was not on strike, was killed at the hands of members of the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, which claimed to represent the bus drivers. The Railroad Trainmen blamed the bus driver, calling him a strikebreaker. The Street Railway & Motor Coach Employees union later won an NLRB representation election, defeating the Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen.

United Mine Workers versus Progressive Mine Workers, 1941

In 1932, some southern Illinois coal miners dissatisfied with the concessions made by the United Mine Workers Union, and what they regarded as the autocratic ways of its leader, John L. Lewis

John Llewellyn Lewis (February 12, 1880 – June 11, 1969) was an American leader of organized labor who served as president of the United Mine Workers of America (UMW) from 1920 to 1960. A major player in the history of coal mining, he was the d ...

, broke away and formed the Progressive Miners of America (PMA), later renamed the Progressive Mine Workers of America

The Progressive Miners of America (PMA, renamed the Progressive Mine Workers of America, PMWA, in 1938) was a coal miners' union organized in 1932 in downstate Illinois. It was formed in response to a 1932 contract proposal negotiated by Unit ...

. The rival unions clashed violently from the start, resulting in numerous deaths on both sides, as well as police officers killed trying to prevent the violence.

The violence was especially intense in southern Illinois in 1932 and 1933, when PMA picketers tried to stop UMWA members from entering the mines. Officers and members of both unions were shot on the street and bombed in their homes. In addition, PMA members set off bombs to stop rail shipments of UMWA-mined coal, trying to force the companies to recognize the PMA. In 1937 the federal government charged 36 PMA members and officers with racketeering, in connection with 44 dynamite explosions at mines and rail facilities. The PMA maintained that the charges resulted from collusion between the FBI, UMWA, and Peabody Coal, and that their methods were no different from those of the UMWA. All 36 were convicted. Although the prison sentences were no more than 16 months, the fines and legal expenses had drained the PMA treasury, and the verdicts labelled the PMA as an outlaw organization.

The Progressive Mine Workers union survived, and PMWA-UMWA violence flared up occasionally over the years, as one union would strike while the other continued to work, and they both claimed to represent miners at various coal mines. In 1946, two miners died in clashes between the rival unions at a mine at Benham, Kentucky, which was represented by the Progressive Mine Workers. In 1982, the Progressive Mine Workers of America represented 4,500 coal miners, compared to the UMWA's membership of 160,000. The union dissolved in 1999.

Legal status

In the United States, union violence often goes unpunished because of pro-union sympathies, or political pressure not to prosecute. A 1966 study cited numerous examples of local and state police failing to interfere with, and state and local prosecutors failing to prosecute, union violence. The authors concluded:

A public official sees many votes on the picket line; few in the office. Perhaps in 1932 it was true that local officials were ignorant of union objectives and brutal in the extreme toward peaceful picketers. Nothing could be further from the truth in 1966.

Although replacement workers have the legal right to be free from violence or intimidation in labor disputes, many law enforcement officials will not interfere with union intimidation, for fear of being accused of being anti-union. When Democratic governor of Arizona Bruce Babbitt sent the national guard to prevent threatened violence by strikers in the Phelps Dodge copper strike of 1982, a union official charged that he was "in the pocket" of Phelps Dodge.

Legal exceptions for labor unions

The US Chamber of Commerce

The United States Chamber of Commerce (USCC) is the largest lobbying group in the United States, representing over three million businesses and organizations. The group was founded in April 1912 out of local chambers of commerce at the urgin ...

has pointed out that a number of states have made legal exceptions for labor disputes in their criminal laws. For example, California, Pennsylvania, Nevada, and Illinois have exempted labor disputes from their laws against stalking.

The Hobbs act makes extortion a federal crime, but under the United States Supreme Court

The Supreme Court of the United States (SCOTUS) is the highest court in the federal judiciary of the United States. It has ultimate appellate jurisdiction over all U.S. federal court cases, and over state court cases that involve a point o ...

's 1973 ''Enmons'' decision (''United States v. Enmons

''United States v. Enmons'', 410 U.S. 396 (1973), was a United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that the federal Anti-Racketeering Act of 1934, known as the Hobbs Act, does not cover union violence in furtherance of the union's ...

''), the actions of union officials in organizing strikes and other united acts of workers are exempt from Hobbs Act prosecutions, as long as the labor dispute is over pay for work performed. This exemption does not confer any immunity from state prosecution for violent acts.

Union policies

No American labor union currently has a policy of openly advocating violence, and some, such as the United Mine Workers in the Pittston Coal strike, have publicly emphasized peaceful means; the UMWA has striking members watch videos about the union's rules to assure peaceful picketing.

Public sympathies

Some union sympathizers believe that labor union violence is justified, especially when directed at strikebreakers. Some hold that the law allowing and protecting strikebreakers is unfair, so that violence and intimidation are the only ways labor unionists can stage an effective strike. Others believe that, although violence is wrong, it should be tolerated as an excess done for the greater good. Clarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the early 20th century for his involvement in the Leopold and Loeb murder trial and the Scopes "Monkey" Trial. He was a leading member of t ...

voiced this view in his courtroom defense of labor leader Big Bill Haywood

William Dudley "Big Bill" Haywood (February 4, 1869 – May 18, 1928) was an American labor organizer and founding member and leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and a member of the executive committee of the Socialist Party of ...

, charged with ordering the assassination of the governor of Idaho:

I don't care how many wrongs they committed, I don't care how many crimes these weak, rough, rugged, unlettered men who often know no other power but the brute force of their strong right arm, who find themselves bound and confined and impaired whichever way they turn, who look up and worship the god of might as the only god that they know--I don't care how often they fail, how many brutalities they are guilty of. I know their cause is just.

Law enforcement sympathies

Examples of local government inaction before or after union violence include the Herrin Massacre, where the county sheriff was a member of the United Mine Workers, and did nothing to prevent or stop the killing of 21 nonstriking workers, after the strikebreakers had given up their weapons on a promise of safe passage out of the county.

Political support

On 12 October 1898, at Virden, Illinois, a crowd of strikers armed with rifles tried to prevent a railroad car of strikebreakers from disembarking, and 8 strikers and 6 strikebreakers died in the gunfight. governor Tanner of Illinois ordered in the National Guard, and on his orders, the following day the Guard prevented the companies from bringing in more strikebreakers. Unable to continue operating, the companies gave in. The governor admitted that he had no legal authority for his action in preventing the arrival of strikebreakers, but said that he was doing the will of the people.

Employer reluctance to press charges

When local, state, or federal officials try to prosecute union violence, they sometimes find that employers are reluctant to cooperate, for fear of union reprisal.

False flags and frameups

False flag

A false flag operation is an act committed with the intent of disguising the actual source of responsibility and pinning blame on another party. The term "false flag" originated in the 16th century as an expression meaning an intentional misr ...

operations are efforts to turn public opinion against an adversary, while pretending to be in the camp of that adversary. Historian J. Bernard Hogg

J. Bernard Hogg (1908–1994) was an American Labor history (discipline), labor historian.

Hogg was the first chairman of the former Shippensburg State College's history/philosophy department and also taught at Indiana University.

Hogg graduat ...

observed of such operations as practiced in 1888:

A detective will join the ranks of the strikers and at once become an ardent champion of their cause. He is next found committing an aggravated assault upon some man or woman who has remained at work, thereby bringing down upon the heads of the officers and members of the assembly or union directly interested, the condemnation of all honest people, and aiding very materially to demoralize the organization and break their ranks.

Some labor spy agencies advertised their false flag operations; for example, Corporations Auxiliary Company, a labor spy agency which boasted 499 corporate clients in the early 1930s, told prospective clients,

In turns extremely radical. He asks for unreasonable things and keeps the union embroiled in trouble. If a strike comes, he will be the loudest man in the bunch, and will counsel violence and get somebody in trouble. The result will be that the union will be broken up.

Johnson County, Indiana

Johnson County is a county located in the U.S. state of Indiana. As of 2020, the population was 161,765. The county seat is Franklin.

Johnson County is included in the Indianapolis-Carmel-Anderson, IN Metropolitan Statistical Area.

Transport ...

Deputy Prosecutor Carlos Lam suggested in an email that Wisconsin's Governor Walker mount a "false flag" operation to make it appear that the union was committing violence in the 2011 Wisconsin protests. After initially claiming that his email account was hacked, Lam admitted to sending the suggestion and resigned.Colorado Labor Wars

The Colorado Labor Wars were a series of labor strikes in 1903 and 1904 in the U.S. state of Colorado, by gold and silver miners and mill workers represented by the Western Federation of Miners (WFM). Opposing the WFM were associations of mi ...

, the Colorado National Guard had been called into the Cripple Creek Mining District to put down a strike, and Colorado National Guard leadership became concerned that the Mine Owners Association In the United States, a Mine Owners' Association (MOA), also sometimes referred to as a Mine Operators' Association or a Mine Owners' Protective Association, is the combination of individual mining companies, or groups of mining companies, into an a ...

had not lived up to their agreement to cover the payroll of the soldiers. In February 1904, General Reardon ordered Major Ellison to shoot up one of the mines. When such violence occurred, the blame would be placed upon the union. In the dark of night, Major Ellison and Sergeant Gordon Walter fired sixty shots from their revolvers into the Vindicator and Lillie shaft house.

See also

* Anti-union violence in the United States

Union busting is a range of activities undertaken to disrupt or prevent the formation of trade unions or their attempts to grow their membership in a workplace.

Union busting tactics can refer to both legal and illegal activities, and can range ...

* Labor spies

Labor spying in the United States had involved people recruited or employed for the purpose of gathering intelligence, committing sabotage, sowing dissent, or engaging in other similar activities, in the context of an employer/labor organization r ...

* Opposition to trade unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

* Union busting

Union busting is a range of activities undertaken to disrupt or prevent the formation of trade unions or their attempts to grow their membership in a workplace.

Union busting tactics can refer to both legal and illegal activities, and can range ...

* Union organizer

A union organizer (or union organiser in Commonwealth spelling) is a specific type of trade union member (often elected) or an appointed union official. A majority of unions appoint rather than elect their organizers.

In some unions, the orga ...

* Union violence Union violence is violence committed by unions or union members during labor disputes. When union violence has occurred, it has frequently been in the context of industrial unrest. Violence has ranged from isolated acts by individuals to wider campa ...

People

* Norris J. Nelson, Los Angeles City Council member, commenting on union violence

* Joseph Yablonski

Joseph Albert "Jock" Yablonski (March 3, 1910 – December 31, 1969) was an American labor leader in the United Mine Workers in the 1950s and 1960s known for seeking reform in the union and better working conditions for miners. In 1969 he c ...

References

External links

BBC report on arrests in the case of Chea Vichea

''The Independent'' report on the murder of Keith Frogson

{{Organized labor

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

Labor relations in the United States

Labor disputes in the United States

The great railroad strike of 1877 saw considerable violence by, and against, workers, and occurred before unions were widespread. It started on July 14 in

The great railroad strike of 1877 saw considerable violence by, and against, workers, and occurred before unions were widespread. It started on July 14 in  In

In